David Schiesser

Spirale

10.06.23–05.07.2023

Spirals and spinal chords

on David Schiesser’s latest works

No matter how different our bodies may look when compared to the bodies of other species, the organization of our anatomy was already decided by the evolution of fish within that wonderful gravity-cancelling element: water. Not only life-giving in what has been called the primordial soup, but gentle and generous in its buoyancy of weights and refraction of lights. No bad knees or sunburns for life in its infancy.

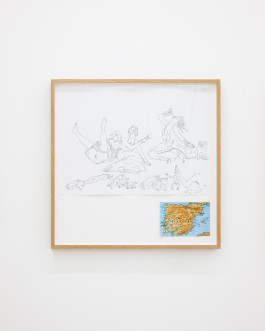

Evolutionary scientists had already perceived the startling similarity between fetuses of different species, from lizards to humans by way of hens and pigs. Differentiation at a specific point kicks, and the genes controlling other genes, like architects and construction works, begin to say: here a fin, there a wing or an arm. This length, that width. This function for specific needs and dangers. It is interesting that in Amerindian Cosmogonies, it is postulated that all beings were first humans, and then became different by wearing different clothes and disguises: here skin, there scales or feathers. When South American indigenous shamans wear the feathers of the harpy eagle or the fur of the jaguar, they reference back to these Cosmogonies. They become those species, and can therefore communicate with them, or, for a moment, cancel the differentiation between beings on the planet. All are humans or all animals, take your pick. What matters is: all are alive.

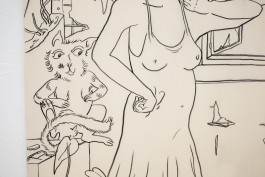

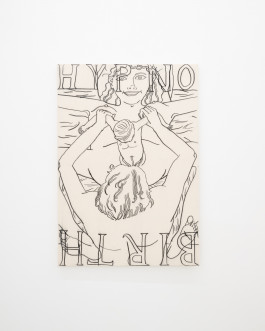

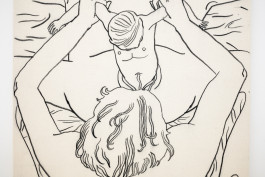

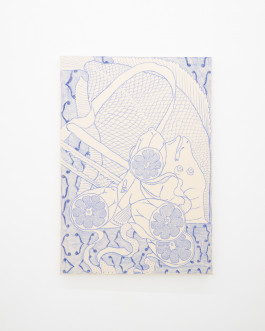

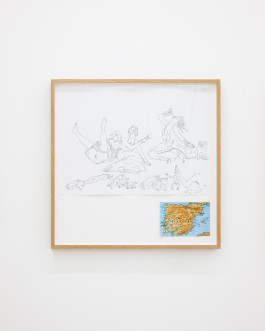

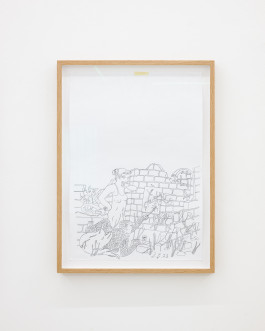

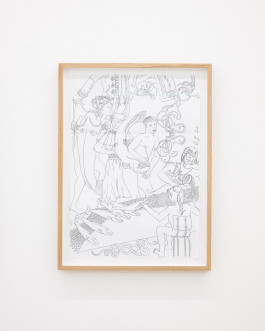

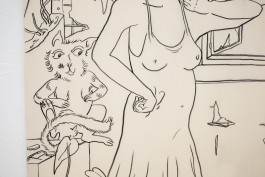

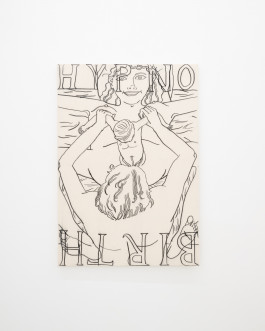

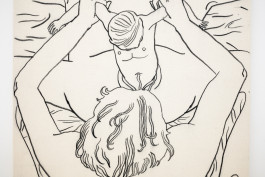

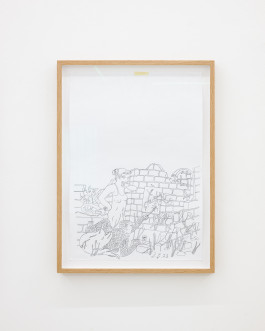

This exhibition of new works by David Schiesser brings several events and images of birth, but also a keen interest in hybridization. And in a transcultural (or should I say transnatural?) aspect, humans with the scales of fish. In one image, a man crawls out of the belly of a fish, as a secular Jonah, a strange prophet who might not look forward, into the future, but back into the past. “Now the LORD had prepared a great fish to swallow up Jonah. And Jonah was in the belly of the fish three days and three nights.” Of course, in the Bible story, Jonah is “vomited upon the land” by the big fish, not cut from it. Our violence between species is not mystical in these works by David Schiesser, but defined by organic hunger and not so organic habits within a market. The mouth is the mother of violence. Teeth were among our first weapons.

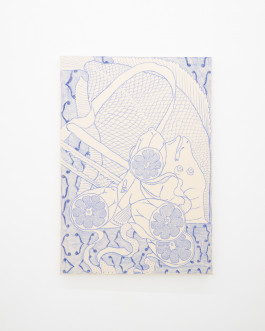

For an artist that has often displayed a particular interest in the dimensionality of bodies, the constant presence of the flatfish brings those notions back, as in previous works where the draughtsman and painter investigated the human skin as grounds for art. The spiral as symbol is totally at home here, indicating even on a flat surface the nature of depth in all things, no matter how minuscule. Our genes also spiral up and down in a double helix.

Spirals are present everywhere in nature. This has often been pointed out, from micro to macro structures: from sea shells to galaxies violently rotating towards black holes at their center. The spiral seems to have fascinated our ancient forefathers and foremothers. They have been found in archeological sites, carved into rocks, or even in gigantic earthworks. In art, it is often recalled as an equation for beauty. Euclid called it “the extreme and mean ratio” and Luca Pacioli called it “the divine proportion”. My apologies, Mr. Pacioli, but we no longer deal in divinities and divinations. We are looking for an escape from that.

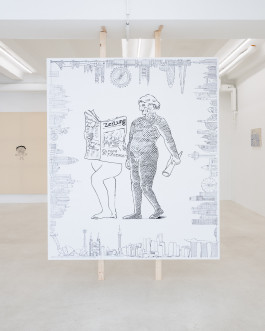

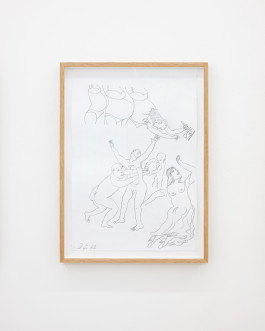

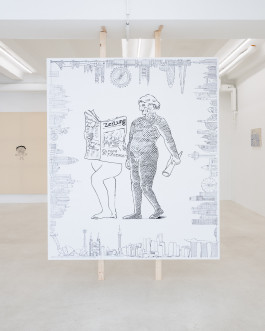

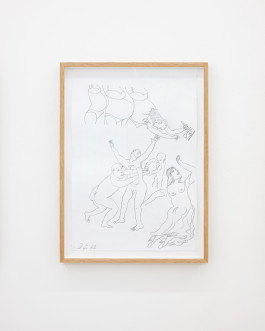

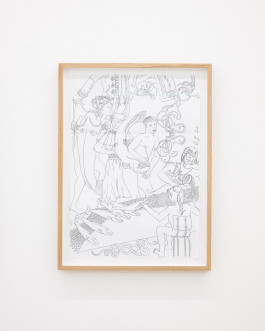

The spiral that one observes within the golden ratio inspired thinkers in the East, like Abu Kamil, and in the West, like Fibonacci. In language art, it is less visible, and I think here of Inger Christensen’s great poem ‘Alphabet’, or W. G. Sebald’s narrative strategies, especially in ‘The Rings of Saturn’. One image in particular attracts me in this show. The lone human figure at the center of a canvas, with a spiral streaming from or into his mouth. Is it centripetal or centrifugal the movement of this spiral? Is the mouth a creator from which we create the World through the Word? Or is that too Judeo-Christian of me? In the Old Testament we have: “And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.” And, in the New Testament’: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” But maybe Schiesser is suggesting a mouth as a black hole, where the spiral ends? It has been noted that many societies had a circular notion of History. It was Judeo-Christian thinking that introduced among us a linear notion of History, with a beginning, and then everything pointing not to its simple end, but to its fulfillment: not the Apocalypse, but the fulfilment of the Messianic promise. The spiral could free us from the particular terrors of both the circular and the linear. We return, but never exactly to the same point. We will get somewhere. Somewhere not too far from who and where we were, are, will be. Is David Schiesser suggesting a new Angel of History, like the one Benjamin derived from Klee’s print. So many storms of terror in History began in and from mouths. But no, no wings, no angels, not anymore, please. Just living creatures and their spiraling sounds.

– Ricardo Domeneck

David Schiesser

Spirale

10.06.23–05.07.2023

Spirals and spinal chords

on David Schiesser’s latest works

No matter how different our bodies may look when compared to the bodies of other species, the organization of our anatomy was already decided by the evolution of fish within that wonderful gravity-cancelling element: water. Not only life-giving in what has been called the primordial soup, but gentle and generous in its buoyancy of weights and refraction of lights. No bad knees or sunburns for life in its infancy.

Evolutionary scientists had already perceived the startling similarity between fetuses of different species, from lizards to humans by way of hens and pigs. Differentiation at a specific point kicks, and the genes controlling other genes, like architects and construction works, begin to say: here a fin, there a wing or an arm. This length, that width. This function for specific needs and dangers. It is interesting that in Amerindian Cosmogonies, it is postulated that all beings were first humans, and then became different by wearing different clothes and disguises: here skin, there scales or feathers. When South American indigenous shamans wear the feathers of the harpy eagle or the fur of the jaguar, they reference back to these Cosmogonies. They become those species, and can therefore communicate with them, or, for a moment, cancel the differentiation between beings on the planet. All are humans or all animals, take your pick. What matters is: all are alive.

This exhibition of new works by David Schiesser brings several events and images of birth, but also a keen interest in hybridization. And in a transcultural (or should I say transnatural?) aspect, humans with the scales of fish. In one image, a man crawls out of the belly of a fish, as a secular Jonah, a strange prophet who might not look forward, into the future, but back into the past. “Now the LORD had prepared a great fish to swallow up Jonah. And Jonah was in the belly of the fish three days and three nights.” Of course, in the Bible story, Jonah is “vomited upon the land” by the big fish, not cut from it. Our violence between species is not mystical in these works by David Schiesser, but defined by organic hunger and not so organic habits within a market. The mouth is the mother of violence. Teeth were among our first weapons.

For an artist that has often displayed a particular interest in the dimensionality of bodies, the constant presence of the flatfish brings those notions back, as in previous works where the draughtsman and painter investigated the human skin as grounds for art. The spiral as symbol is totally at home here, indicating even on a flat surface the nature of depth in all things, no matter how minuscule. Our genes also spiral up and down in a double helix.

Spirals are present everywhere in nature. This has often been pointed out, from micro to macro structures: from sea shells to galaxies violently rotating towards black holes at their center. The spiral seems to have fascinated our ancient forefathers and foremothers. They have been found in archeological sites, carved into rocks, or even in gigantic earthworks. In art, it is often recalled as an equation for beauty. Euclid called it “the extreme and mean ratio” and Luca Pacioli called it “the divine proportion”. My apologies, Mr. Pacioli, but we no longer deal in divinities and divinations. We are looking for an escape from that.

The spiral that one observes within the golden ratio inspired thinkers in the East, like Abu Kamil, and in the West, like Fibonacci. In language art, it is less visible, and I think here of Inger Christensen’s great poem ‘Alphabet’, or W. G. Sebald’s narrative strategies, especially in ‘The Rings of Saturn’. One image in particular attracts me in this show. The lone human figure at the center of a canvas, with a spiral streaming from or into his mouth. Is it centripetal or centrifugal the movement of this spiral? Is the mouth a creator from which we create the World through the Word? Or is that too Judeo-Christian of me? In the Old Testament we have: “And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.” And, in the New Testament’: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” But maybe Schiesser is suggesting a mouth as a black hole, where the spiral ends? It has been noted that many societies had a circular notion of History. It was Judeo-Christian thinking that introduced among us a linear notion of History, with a beginning, and then everything pointing not to its simple end, but to its fulfillment: not the Apocalypse, but the fulfilment of the Messianic promise. The spiral could free us from the particular terrors of both the circular and the linear. We return, but never exactly to the same point. We will get somewhere. Somewhere not too far from who and where we were, are, will be. Is David Schiesser suggesting a new Angel of History, like the one Benjamin derived from Klee’s print. So many storms of terror in History began in and from mouths. But no, no wings, no angels, not anymore, please. Just living creatures and their spiraling sounds.

– Ricardo Domeneck

Get in contact or

book an appointment

Schirmerstrasse 61

Backyard

40211 Duesseldorf

Germany

Follow us on Instagram, or subscribe to our newsletter to receive invitations to upcoming exhibition openings and more information about featured artists.

Get in contact or

book an appointment

Schirmerstrasse 61

Backyard

40211 Duesseldorf

Germany

Follow us on Instagram, or subscribe to our newsletter to receive invitations to upcoming exhibition openings and more information about featured artists.