ebd. o. so

groupshow

curated by Jenny Brosinski

Mar 22, 2024–May 18, 2024

ebd. o. so

Abstraction is often conceived as the polar opposite of figuration. This perception of extreme difference has to do with the fact that figurative artworks attempt to capture the world in a realistic and naturalistic way, whereas abstract artworks avoid direct representation, instead aiming to express what lies beneath appearances. But the old binary between figuration and abstraction overshadows that, just like the poles of a magnet, these styles lie on a continuum and interact with one another. Abstract artists find occasion in figuration, and vice versa.

Art can and frequently does oscillate between abstraction and figuration. Figurative painting may incorporate characteristics of abstraction, such as unconventional use of colour and the distortion of forms, to convey a deeper meaning. Equally, abstract painting may contain hints of vague shapes that suggest something recognizable, even if it is not explicitly depicted. This genre fuzziness is conveyed in the exhibition title ebd. o. so, shorthand for “ebenda oder so” (ibidem or so). The line between abstraction and figuration is not precisely known but rather negotiated within the artworks on show and within the artists’ Jenny Brosinski, Sascha Brylla, and Matthias Dornfeld bodies of work.

The exhibition ebd. o. so begins with the premise that abstraction and figuration coexist and influence each other in different ways. The second premise is that abstraction and figuration follow each other, transforming themselves through the gestures, techniques, and concepts of artists. The three positions presented at JVDW gallery – Jenny Brosinski, Sascha Brylla, and Matthias Dornfeld – show each in their unique way how figurative elements and associations presuppose the abstract work, opening up new perspectives on what abstraction is and how it can come into being.

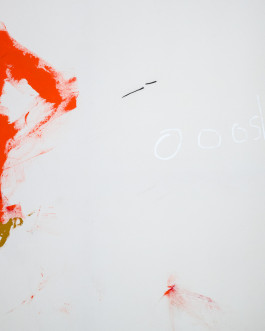

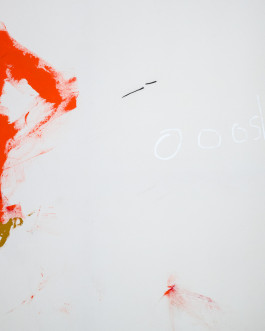

According to the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, figuration is a “prerequisite of painting”, as various mediums like photographs, newspapers, cinema, and television create perceptions, memories, and phantasms (“cliches”) that preoccupy the canvas even before the process of painting begins. Jenny Brosinski plays with these cliches, but not by superficially abstracting their content. Instead, she examines the properties, colours, and textures that the figurative evokes. When projecting these from her mind to the canvas, Brosinski pays special attention to the relationship among formal features, or the “negative space”, as she calls it. How much white surface is too little, or too much? Where is the threshold beyond which the work loses its pictorial tension? Tension, Deleuze argues, is precisely what gives abstraction a depth and complexity exceeding that of geometric shapes. In Brosinki’s work, tension is upheld through the painterly gesture.

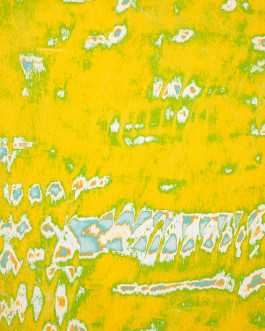

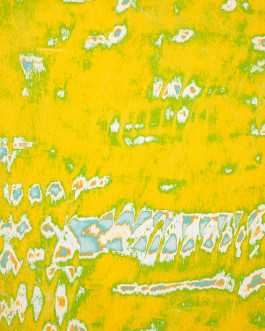

The painterly gesture is also central to the work of Sascha Brylla. But, in his case, it is the act of removing rather than re/arranging that deconstructs and reconstitutes figurative imagery into abstraction. After priming the canvas, Brylla graphically depicts an identifiable object or being that he gives center stage. This is at once his “protagonist” and a “placeholder”, as he calls it. Through a sculptural process of scratching away layers of paint, Brylla gradually strips away visual information and creates increasingly more illegible, abstract paintings. Here, too, there is a tipping point. Too little scraping will leave the figurative element overly prominent, detracting from the intended abstraction. Too much scraping risks erasing the essence of the subject altogether, resulting in a loss of cohesion or, as Brylla says, a “point of no return”. The delicate balance lies in his ability to maintain just enough detail to evoke what is known while allowing the abstraction to enchant the viewer to look for clues and layer their own meaning onto the work.

Matthias Dornfeld is less concerned with achieving a sense of equilibrium but rather focuses on synthesising seemingly disparate but in fact tightly connected domains – abstraction and figuration – to create a unified whole. His paintings are probably the most contradictory and difficult to describe, as they are mixed and eclectic in their use of genre and style. Sometimes Dornfeld begins by painting abstract and segues into figuration; at other times he shifts from abstraction to a higher level of abstraction, as we see with the line paintings showcased. This categorical ambiguity extends from his approach to his artworks. Take the painting of a wine-coloured figure wearing a pleated skirt as an example. The white thick lines are both ‘pure’ in the sense of representing themselves and referential in that they hint at something ‘real’ like a pedestal. This duality is bridged by what Dornfeld calls a “strange fabric” holding everything together. Similar to Brosinski’s tension, Dornfeld’s fabric is woven at the level of the paintery line, expressing a logic of painting as process.

JVDW gallery is delighted to present the exhibition ebd. o. so, curated by Jenny Brosinksi. On show are works by Jenny Brosinksi, Sascha Brylla, and Matthias Dornfeld. The exhibition runs from March 22 to May 5, 2024.

– text by Merit Zimmermann

ebd. o. so

groupshow

curated by Jenny Brosinski

Mar 22, 2024–May 18, 2024

ebd. o. so

Abstraction is often conceived as the polar opposite of figuration. This perception of extreme difference has to do with the fact that figurative artworks attempt to capture the world in a realistic and naturalistic way, whereas abstract artworks avoid direct representation, instead aiming to express what lies beneath appearances. But the old binary between figuration and abstraction overshadows that, just like the poles of a magnet, these styles lie on a continuum and interact with one another. Abstract artists find occasion in figuration, and vice versa.

Art can and frequently does oscillate between abstraction and figuration. Figurative painting may incorporate characteristics of abstraction, such as unconventional use of colour and the distortion of forms, to convey a deeper meaning. Equally, abstract painting may contain hints of vague shapes that suggest something recognizable, even if it is not explicitly depicted. This genre fuzziness is conveyed in the exhibition title ebd. o. so, shorthand for “ebenda oder so” (ibidem or so). The line between abstraction and figuration is not precisely known but rather negotiated within the artworks on show and within the artists’ Jenny Brosinski, Sascha Brylla, and Matthias Dornfeld bodies of work.

The exhibition ebd. o. so begins with the premise that abstraction and figuration coexist and influence each other in different ways. The second premise is that abstraction and figuration follow each other, transforming themselves through the gestures, techniques, and concepts of artists. The three positions presented at JVDW gallery – Jenny Brosinski, Sascha Brylla, and Matthias Dornfeld – show each in their unique way how figurative elements and associations presuppose the abstract work, opening up new perspectives on what abstraction is and how it can come into being.

According to the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, figuration is a “prerequisite of painting”, as various mediums like photographs, newspapers, cinema, and television create perceptions, memories, and phantasms (“cliches”) that preoccupy the canvas even before the process of painting begins. Jenny Brosinski plays with these cliches, but not by superficially abstracting their content. Instead, she examines the properties, colours, and textures that the figurative evokes. When projecting these from her mind to the canvas, Brosinski pays special attention to the relationship among formal features, or the “negative space”, as she calls it. How much white surface is too little, or too much? Where is the threshold beyond which the work loses its pictorial tension? Tension, Deleuze argues, is precisely what gives abstraction a depth and complexity exceeding that of geometric shapes. In Brosinki’s work, tension is upheld through the painterly gesture.

The painterly gesture is also central to the work of Sascha Brylla. But, in his case, it is the act of removing rather than re/arranging that deconstructs and reconstitutes figurative imagery into abstraction. After priming the canvas, Brylla graphically depicts an identifiable object or being that he gives center stage. This is at once his “protagonist” and a “placeholder”, as he calls it. Through a sculptural process of scratching away layers of paint, Brylla gradually strips away visual information and creates increasingly more illegible, abstract paintings. Here, too, there is a tipping point. Too little scraping will leave the figurative element overly prominent, detracting from the intended abstraction. Too much scraping risks erasing the essence of the subject altogether, resulting in a loss of cohesion or, as Brylla says, a “point of no return”. The delicate balance lies in his ability to maintain just enough detail to evoke what is known while allowing the abstraction to enchant the viewer to look for clues and layer their own meaning onto the work.

Matthias Dornfeld is less concerned with achieving a sense of equilibrium but rather focuses on synthesising seemingly disparate but in fact tightly connected domains – abstraction and figuration – to create a unified whole. His paintings are probably the most contradictory and difficult to describe, as they are mixed and eclectic in their use of genre and style. Sometimes Dornfeld begins by painting abstract and segues into figuration; at other times he shifts from abstraction to a higher level of abstraction, as we see with the line paintings showcased. This categorical ambiguity extends from his approach to his artworks. Take the painting of a wine-coloured figure wearing a pleated skirt as an example. The white thick lines are both ‘pure’ in the sense of representing themselves and referential in that they hint at something ‘real’ like a pedestal. This duality is bridged by what Dornfeld calls a “strange fabric” holding everything together. Similar to Brosinski’s tension, Dornfeld’s fabric is woven at the level of the paintery line, expressing a logic of painting as process.

JVDW gallery is delighted to present the exhibition ebd. o. so, curated by Jenny Brosinksi. On show are works by Jenny Brosinksi, Sascha Brylla, and Matthias Dornfeld. The exhibition runs from March 22 to May 5, 2024.

– text by Merit Zimmermann

Get in contact or

book an appointment

Schirmerstrasse 61

Backyard

40211 Duesseldorf

Germany

Follow us on Instagram, or subscribe to our newsletter to receive invitations to upcoming exhibition openings and more information about featured artists.

Get in contact or

book an appointment

Schirmerstrasse 61

Backyard

40211 Duesseldorf

Germany

Follow us on Instagram, or subscribe to our newsletter to receive invitations to upcoming exhibition openings and more information about featured artists.